| EMAIL NPM tel: 503.233.0512 | |||

| site search by freefind | advanced | ||

Allan Martin, born 1954 in San Francisco, grew up in Oregon. He studied piano and composition with the Czech composer Tomas Svoboda in Portland, Oregon, with Claire James, Robert Sheldon and John Adams at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and with Colin Horsley and Edwin Roxburgh in London, and has concertized and taught piano near Stuttgart, Germany for over thirty years. He specializes in playing historical pianos from the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries. A previous CD of his, Everything is Ragtime Now, recorded with the Oregon ensemble De Organographia, appeared on the Pandourion label.

Anyone reading the letters of Fryderyk Chopin for the first time will, I think, be surprised at how unromantic they are. Chopin’s style is clear, direct, with a sense for social satire of the sort to be found in the works of Jane Austen, marked by occasional blackly humorous barbs against himself. And it is notable – for all that we find out about the man’s daily life at any given time, his praise for opera productions for example, or preference for certain singers – how very little we find out about what made this reserved, cultivated Pole produce the sort of music that he did: music which even his admirer Robert Schumann sometimes found too chromatic, too drastic. “In the country of his birth and its fate lies the explanation both of his merits and his faults,” wrote Schumann. “Who will not be reminded of him when we use the words Visionary, Grace, Presence of Mind, Ardour, and Aristocracy, but who as well when we use the words Strangeness, Morbid Eccentricity, even Animosity and Wildness?”

|

| track samples - 60 sec.

|

|

Mazurkas op. 63 (1846) |

|

|

2. II Lento F minor |

|

|

3. Allegretto C sharp minor |

|

|

Nocturnes op. 32 (1836/37) |

|

|

5. Lento A flat major |

|

|

Etude op. 10 No. 5 G flat major (1830)

| |

|

6. Vivace |

|

|

Polonaises op. 26 (1834/35) |

|

|

8. Maestoso E flat minor |

|

|

9. Vivace A-flat major |

|

|

10. Lento A minor |

|

|

11. Vivace F major |

|

|

Nocturne op. 62 No. 2 E major (1834/35) |

|

|

Ballade No. 3 op. 47 A-flat major (1841) |

|

|

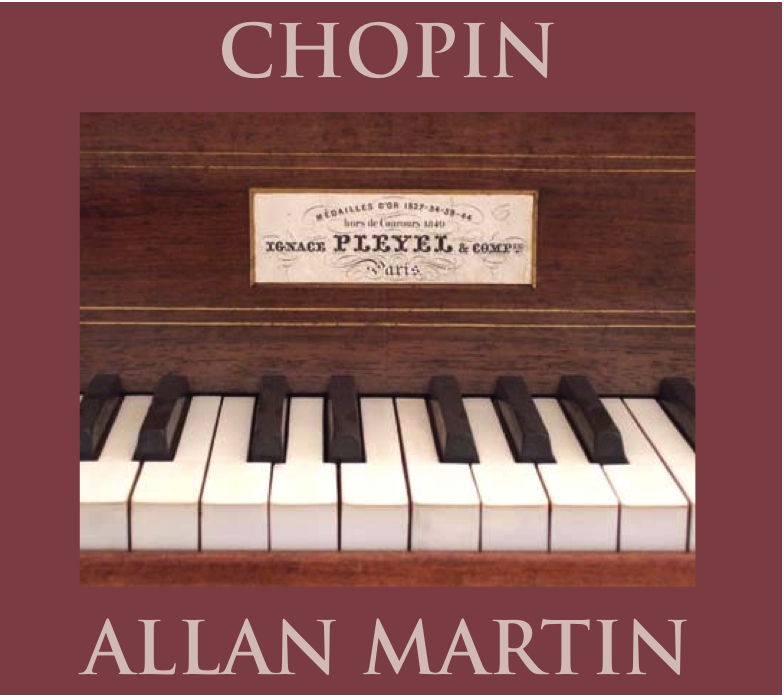

Pleyel grand piano built in 1849, restored by Stefan Schneider,

recorded in Stuttgart, Germany in November 2009 and February 2010 in the workshop of Stefan Schneider.

About the piano

The composer Ignaz Joseph Pleyel, born near Vienna in 1757, founded in 1807 one of the most famous and important piano manufacturing companies in France. Pleyel’s son Camille became a business partner in 1815, and in the 1820s – working closely with famous artists of the time – took the leading role in the successful direction of the company. The production rooms in Paris had to be enlarged repeatedly. In 1830 the Salle Pleyel opened its doors.

|